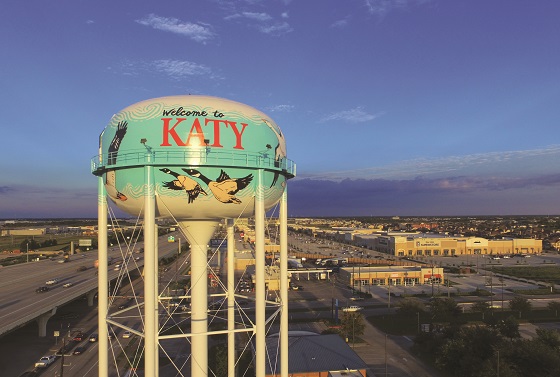

Located ~20 miles (32.2 km) west of Houston, Texas, one of the most visible water tanks in the City of Katy is a 500,000-gallon (1.89 million L) structure next to Interstate 10 (I-10). The tank’s exterior coatings are subject to atmospheric degradation owing to tropical conditions on the U.S. Gulf Coast, while interior coatings can corrode due to humidity from cooler water temperatures relative to outside air temperatures, as well as erosion from water cycling through the tanks.

Clark Northup, owner of nearby STW & Inspections, LLC, has inspected Katy’s water tanks annually since 2006. By 2017, both the interior and exterior coatings of the elevated I-10 tank showed signs of degradation, with the carbon steel substrate displaying some corrosion. The tank was last coated about 15 years earlier, so its needs included draining and recoating the interior and exterior, as well as recoating the exterior of supporting steel columns and the interior and exterior of center risers.

“For years, the city had let the tanks go,” Northup said. “But they hit a brick wall. They knew they had to rehabilitate the tanks.” A&M Construction and Utilities, led by vice president of tank rehab Rick Thorn, was contracted to coat the I-10 tank, which stands at 135-feet (41.2 m) tall and 56 feet (17.1 m) in diameter.

Hurricane Proof

Safety was an obvious priority for the highly visible project, both for the six crew members at the jobsite and the surrounding area. Standard personal protective equipment (PPE) was worn by workers, such as hard hats, safety glasses, gloves, work boots, and respiratory protection. The crew used stages from Spider with personal fall arrest systems to access higher areas, along with ladders as needed

The highly trafficked area required extra precautions. Since specifications called for zero-emissions containment, the tank was completely covered during blasting and painting. This involved a stationary covering, or bonnet, attached to the tank’s top, and lateral curtains —raised and lowered more than 100 feet (30.5 m) daily with hoists — surrounding both the tank as well as the steel columns and riser. Due to the area’s windy conditions, crew members often had to stitch the containment back together. “The bonnet gets ripped at night, and every morning the workers go up and fix it,” Northup said.

Partly by design, the crew caught a relative break with the job’s phasing. The project was awarded in mid-2017, which is the start of hurricane season on the Gulf Coast. Based on inclement weather that July, the crew began the multi-month assignment by working on the tank’s interior.

By mid-August, when it became clear that effects from Hurricane Harvey were headed to the area, this significantly assisted their demobilization efforts. The historic storm ultimately dumped more than 50 inches (127.0 cm) of rain on parts of the region, which brought work to a standstill for weeks. However, it easily could have been worse.

According to Thorn, the tank’s exterior had yet to be blasted, which would have left bare metal exposed to the elements and the structure subject to rapid corrosion. Instead, because they started inside, all they needed to do was take down containment. Thus, once it was safe to return by late September, they quickly resumed work on the project.

Inside and Out

One unique aspect to this job was that it required two separate coating systems, according to coatings consultant Pat Barry, who represented Tnemec as the manufacturer. Both the interior and exterior received a spray-applied zinc-rich urethane primer, Series 90-97 Tneme-Zinc, but then each took a different path.

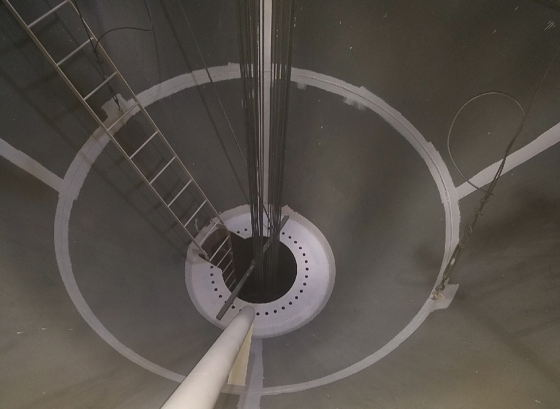

For the interior, a high-build epoxy coating system was selected to address erosion concerns. “With that much surface water going in, it erodes the coatings,” Northup said. After priming, the interior system received a stripe coat and full spray-applied coat of Series 141 Epoxoline. The total interior dry film thickness (DFT) was 20 to 25 mils (508.0–635.0 microns).

Meanwhile, the four-coat exterior system at approximately 12 mils (304.8 microns) combined DFT, included the primer; a stripe coat and roller-applied intermediate coat of Series 20 polyamide epoxy with high-build edge protection and abrasion resistance for immersion service; a roller-applied coat of the Series 73 Endura-Shield acrylic polyurethane; and a finish coat of Tnemec’s fluoropolymer topcoat, the Series 700 HydroFlon. According to the manufacturer, Series 700 is formulated to provide long-term color and gloss retention and can resist the effects of ultraviolet (UV) light degradation.

Using Schmidt blasting equipment, the tank’s interior surface was blasted with white sand, while exterior surfaces were blasted with coal slag at a pressure of 32 psi (221.0 kPa) to achieve the NACE No. 2/Society for Protective Coatings (SSPC) Surface Preparation (SP) 10: Near-White Blast Cleaning standard. For the 4-foot (1.2 m) diameter riser, a bosun’s chair was used to vertically raise and lower a worker to blast and coat the internal surface. The exterior was blasted and painted in sections to ensure the freshly blasted steel was quickly primed.

“The primer locks in the blast and protects the metal surface from the elements,” Thorn said. Each section was pressure washed to remove atmospheric contaminants; allowed to dry; blasted; and then primed on the same day. Typically, the crew would blast the steel until about mid-afternoon, blow down the area to be coated, and then apply the primer.

“If we missed that window and left the bare metal exposed overnight, chances are it would have begun corroding by morning,” Thorn explained. “Then we would have to re-blast the surface to knock off the bloom.”

The persistent challenge was avoiding issues with Houston’s notoriously high humidity. According to Northup, if the humidity and dew point are too high, condensation can form on the surfaces to be coated and lead to premature failure. This meant that work often did not begin until humidity levels were acceptable for coating, which often delayed the crew’s start until mid-day. In addition, to avoid the potential overnight ingress of atmospheric contaminants between layers, the exterior surface was pressure washed daily before a new coating layer was applied.

Work of Art

By November 2017, with a grand total of 639 gallons (2,418.9 L) of coating, the A&M crew completed the tank and had it ready for the city’s finishing touch — a mural of flying geese to commemorate the migratory birds that winter in the area. The 20-feet-tall (6.1 m) geese murals were designed by a specialist contractor from the State of Washington named Artistbrothers, who applied the murals by roller using the Series 700 fluoropolymer in a variety of colors.

The A&M crew was held to a tight timetable throughout their project, since the murals specialist from across the country was contracted to paint both the I-10 water tank and a separate Katy tank on the same December 2017 trip. In other words, the A&M crew had to finish on a similar timetable to a separate contractor that was working on a smaller 250,000-gallon (~946,353.0 L) water tank and adjacent ground-level storage tank at a nearby residential community. Both jobs, of course, were briefly stalled due to Harvey.

Besides the contractor, Barry also credited Northup with helping keep both jobs in line. “The consultant, STW, did a pretty good job at getting both contractors to finish around the same time so the muralists could do both tanks in one trip,” Barry said.

After the muralists successfully completed their work, praise for the combined job extended well beyond just client and manufacturer. Less than a year later, the two tanks were jointly honored as the 2018 winner of Tnemec’s annual Tank of the Year competition. The tanks were selected by a panel of water tank enthusiasts who based their decision on criteria such as artistic value, the tank’s community significance, and challenges encountered. More than 270 U.S. and Canadian tanks were considered for the award.

But the biggest winner of all could be the residents of Katy, who are poised to benefit from the revamped tanks. “I’m not having near as much staining and corrosion on the inside of these tanks,” Northup said. “When contractors do their part, coatings do their part, and the water is cleaner. It takes more chlorine to kill that bacteria, which costs more money.”

Editor’s note: The Katy water tanks job was also featured in the January 2019 issue of Materials Performance (MP) Magazine.